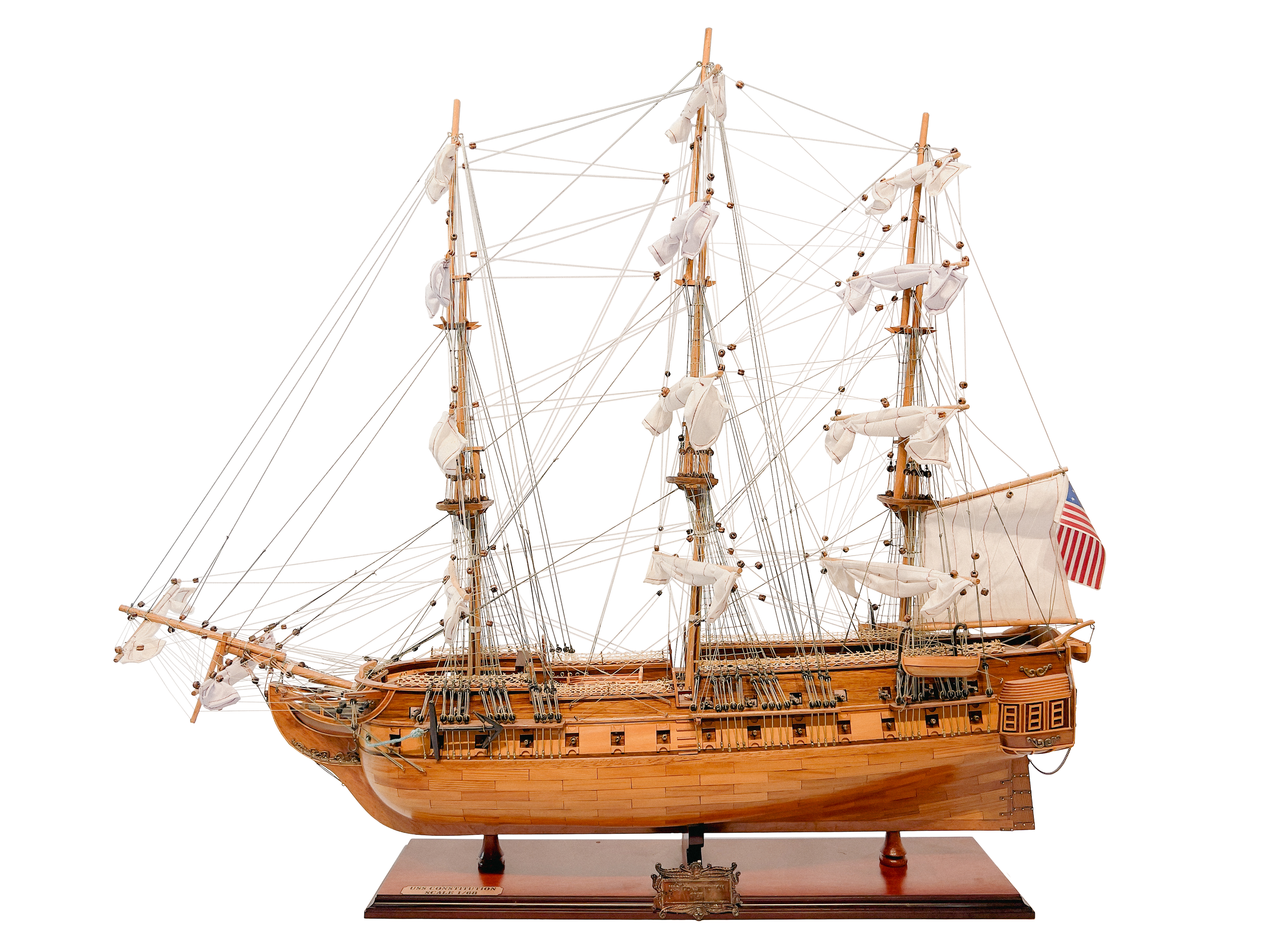

zoom in on model

1780

Fragata Espanola

Scale 1/45

Credit: Museum of Military Models, Clyde, Texas. Private Collection of Warren D. Harkins.ON VIEW

General Characteristics

Class and type:

Frigate

Description

During the 17th century, and for much of the first half of the 18th century, the term 'frigate' (or 'fragata' in Spanish) encompassed ships with two complete gundecks rated at about 50 guns as well as smaller single-decked vessels. The smaller frigates evolved from the fast and lightly-armed vessels built chiefly on the coast of (Spanish) Flanders, and employed in the English Channel and southern North Sea, as well as escorting the trade routes from the Spanish Netherlands to the north coast of Spain. The plaque on the base of the stand for the ship reads: Fragata Espanola Ano 1780. She was one of the Spanish ships that fought in the battle of Cape St. Vincent, which took place off the southern coast of Portugal on 16 January 1780 during the American Revolutionary War.

Example of a Spanish Frigate: Fragata Nuestra Senora del Carmen 1780.Ownership & Province

-

Name: Fragata Espanola

Built: Unknown

Launched: Unknown (Around 1780)

Fate: Unknown

History & Related Content

Service History

Battle of Cape St. Vincent (1780)

There is evidence that this ship was one of the Spanish ships that fought in the battle of Cape St. Vincent, which took place off the southern coast of Portugal on January 16, 1780 during the American Revolutionary War. It was one of the opening battles of the Anglo-Spanish War, as part of the French Revolutionary Wars, where a British fleet under Admiral Sir John Jervis defeated a greatly superior Spanish fleet under Admiral Don José de Córdoba y Ramos near Cape St. Vincent, Portugal.

Description

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent (Spanish: Batalla del Cabo de San Vicente) was a naval battle that took place off the southern coast of Portugal on 16 January 1780 during the American Revolutionary War. A British fleet under Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated a Spanish squadron under Don Juan de Lángara. The battle is sometimes referred to as the Moonlight Battle (batalla a la luz de la luna) because it was unusual for naval battles in the Age of Sail to take place at night. It was also the first major naval victory for the British over their European enemies in the war and proved the value of copper-sheathing the hulls of warships.

Rodney was escorting a fleet of supply ships to relieve the Spanish siege of Gibraltar with a fleet of about twenty ships of the line when he encountered Lángara's squadron south of Cape St. Vincent. When Lángara saw the size of the British fleet, he attempted to make for the safety of Cádiz, but the copper-sheathed British ships chased his fleet down. In a running battle that lasted from mid-afternoon until after midnight, the British captured four Spanish ships, including Lángara's flagship Real Fénix (often just called "Fenix"). Two other ships were also captured, but they were retaken by their Spanish crews, although Rodney's report claimed the ships were grounded and destroyed; in fact one went aground and was destroyed, while the other safely returned to Cadiz and resumed service with the Spanish Navy.

After the battle Rodney successfully resupplied Gibraltar and Minorca before continuing on to the British West Indies. Lángara was released on parole; his career did not suffer from the defeat, and he was promoted to lieutenant general by Charles III of Spain.

Background

One of Spain's principal goals upon its entry into the American War of Independence in 1779 was the recovery of Gibraltar, which had been lost to Great Britain in 1704. The Spanish planned to retake Gibraltar by blockading and starving out its garrison, which included troops from Britain and the Electorate of Hanover. The siege formally began in June 1779, with the Spanish establishing a land blockade around the Rock of Gibraltar. The matching naval blockade was comparatively weak, however, and the British discovered that small fast ships could evade the blockaders, while slower and larger supply ships generally could not. By late 1779, however, supplies in Gibraltar had become seriously depleted, and its commander, General George Eliott, appealed to London for relief. A supply convoy was organized, and in late December 1779 a large fleet sailed from England under the command of Admiral Sir George Rodney. Although Rodney's ultimate orders were to command the West Indies fleet, he had secret instructions to first resupply Gibraltar and Minorca. On 4 January 1780 the fleet divided, with ships headed for the West Indies sailing westward. This left Rodney in command of 19 ships of the line, which were to accompany the supply ships to Gibraltar.

On 8 January 1780 ships from Rodney's fleet spotted a group of sails. Giving chase with their faster copper-clad ships, the British determined these to be a Spanish supply convoy that was protected by a single ship of the line and several frigates. The entire convoy was captured, with the lone ship of the line, Guipuzcoana, striking her colours after a perfunctory exchange of fire. Guipuzcoana was staffed with a small prize crew and renamed HMS Prince William, in honour of Prince William, the third son of the King, who was serving as midshipman in the fleet. Rodney then detached HMS America and the frigate HMS Pearl to escort most of the captured ships back to England; Prince William was added to his fleet, as were some of the supply ships that carried items likely to be of use to the Gibraltar garrison.

On 12 January HMS Dublin, which had lost part of her topmast on 3 January, suffered additional damage and raised a distress flag. Assisted by HMS Shrewsbury, she limped into Lisbon on 16 January. The Spanish had learnt of the British relief effort. From the blockading squadron a fleet comprising 11 ships of the line under Admiral Juan de Lángara was dispatched to intercept Rodney's convoy, and the Atlantic fleet of Admiral Luis de Córdova y Córdova at Cadiz was also alerted to try to catch him. Córdova learnt of the strength of Rodney's fleet, and returned to Cadiz rather than giving chase. On 16 January the fleets of Lángara and Rodney spotted each other around 1:00 pm south of Cape St. Vincent, the southwestern point of Portugal and the Iberian Peninsula. The weather was hazy, with heavy swells and occasional squalls.

Battle

Rodney was ill, and spent the entire action in his bunk. His flag captain, Walter Young, urged Rodney to give orders to engage when the Spanish fleet was first spotted, but Rodney only gave orders to form a line abreast. Lángara started to establish a line of battle, but when he realised the size of Rodney's fleet, he gave orders to make all sail for Cadiz. Around 2:00 pm, when Rodney felt certain that the ships seen were not the vanguard of a larger fleet, he issued commands for a general chase. Rodney's instructions to his fleet were to chase at their best speed, and engage the Spanish ships from the rear as they came upon them. They were also instructed to sail to the lee side to interfere with Spanish attempts to gain the safety of a harbour, a tactic that also prevented the Spanish ships from opening their lowest gun ports. Because of their copper-sheathed hulls (which reduced marine growths and drag), the ships of the Royal Navy were faster and soon gained on the Spanish.

The chase lasted for about two hours, and the battle finally began around 4:00 pm. Santo Domingo, trailing in the Spanish fleet, received broadsides from HMS Edgar, HMS Marlborough, and HMS Ajax before blowing up around 4:40, with the loss of all but one of her crew. Marlborough and Ajax then passed Princessa to engage other Spanish ships. Princessa was eventually engaged in an hour-long battle with HMS Bedford before striking her colours at about 5:30. By 6:00 pm it was getting dark, and there was a discussion aboard HMS Sandwich, Rodney's flagship, about whether to continue the pursuit. Although Captain Young is credited in some accounts with pushing Rodney to do so, Gilbert Blane, the fleet physician, reported it as a decision of the council.

The chase continued into the dark, squally night, leading to it later being known as the "Moonlight Battle", since it was uncommon at the time for naval battles to continue after sunset. At 7:30 pm, HMS Defence came upon Lángara's flagship Fenix, engaging her in a battle lasting over an hour. She was broadsided in passing by HMS Montagu and HMS Prince George, and Lángara was wounded in the battle. The Real Fénix finally surrendered to HMS Bienfaisant, which arrived late in the battle and shot away her mainmast. Real Fénix's takeover was complicated by an outbreak of smallpox aboard Bienfaisant. Captain John MacBride, rather than sending over a possibly infected prize crew, apprised Lángara of the situation and put him and his crew on parole. At 9:15 Montagu engaged Diligente, which struck after her maintopmast was shot away. Around 11:00 pm San Eugenio surrendered after having all of her masts shot away by HMS Cumberland, but the difficult seas made it impossible to board a prize crew until morning.

That duel was passed by HMS Culloden and Prince George, which engaged San Julián and compelled her to surrender around 1:00 am. The last ship to surrender was Monarca. She nearly escaped, shooting away HMS Alcide's topmast, but was engaged in a running battle with the frigate HMS Apollo. Apollo managed to keep up the unequal engagement until about the time that Rodney's flagship Sandwich came upon the scene around 2:00 am. Sandwich fired a broadside, unaware that Monarca had already hauled down her flag. The British took six ships. Four Spanish ships of the line and the fleet's two frigates escaped, although sources are unclear if two of the Spanish ships were even present with the fleet at the time of the battle. Lángara's report states that San Justo and San Genaro were not in his line of battle (although they are listed in Spanish records as part of his fleet). According to one account two of Lángara's ships (the two aforementioned) were despatched to investigate other unidentified sails sometime before the action. Rodney's report states that San Justo escaped but was damaged in battle, and that San Genaro escaped without damage.

Don Juan de Lángara, portrait by an unknown artist. Unknown author - Retrato de Juan de Lángara y Huarte (1736-1806) - Anónimo.Admiral Sir George Rodney, portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds.The Moonlight Battle by Dominic Serres, 1781.La Battalla de Cabo de San Vincente, painted by an unknown Spanish artist.The Moonlight Battle off Cape St. Vincent, 16 January 1780, by Richard Paton.Aftermath

With the arrival of daylight, it was clear that the British fleet and their prize ships were dangerously close to a lee shore with an onshore breeze. One of the prizes, San Julián, was recorded by Rodney as too badly damaged to save, and was driven ashore. Another prize, San Eugenio, was retaken by her crew and managed to reach Cadiz; she was later restored to service within two months, and remained so until taken to pieces at Cadiz in 1804. A Spanish history claims that the prize crews of both ships appealed to their Spanish captives for help escaping the lee shore. The Spanish captains retook control of their ships, imprisoned the British crews, and sailed to Cadiz. The British reported their casualties in the battle as 32 killed and 102 wounded. The supply convoy sailed into Gibraltar on 19 January, driving the smaller blockading fleet to retreat to the safety of Algeciras. Rodney arrived several days later, after first stopping in Tangier. The wounded Spanish prisoners, who included Lángara, were offloaded there, and the British garrison was heartened by the arrival of the supplies and the presence of Prince William Henry.

After also resupplying Minorca, Rodney sailed for the West Indies in February, detaching part of the fleet for service in the Channel. This homebound fleet intercepted a French fleet destined for the East Indies, capturing one warship and three supply ships. Gibraltar was resupplied twice more before the siege was lifted at the end of the war in 1783. Lángara and other captured Spanish officers were eventually released on parole, with Charles III of Spain promoting Lángara to lieutenant general. He continued to serve in the Spanish navy, being appointed as the naval minister during the French Revolutionary Wars. Rodney was lauded for his victory, the first major victory of the war by the Royal Navy over its European opponents. He distinguished himself for the remainder of the war, notably winning the 1782 Battle of the Saintes in which he captured French Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse. He was, however, criticised by Captain Young, who portrayed him as weak and indecisive in the battle with Lángara. (He was also rebuked by the admiralty for leaving a ship of the line at Gibraltar, against his express orders.) Rodney's observations on the benefits of copper sheathing in the victory were influential in British Admiralty decisions to deploy the technology more widely.

Rodney's Fleet Taking in Prizes After the Moonlight Battle, 16 January 1780, by Dominic Serres. Dominic Serres - National Maritime Museum.