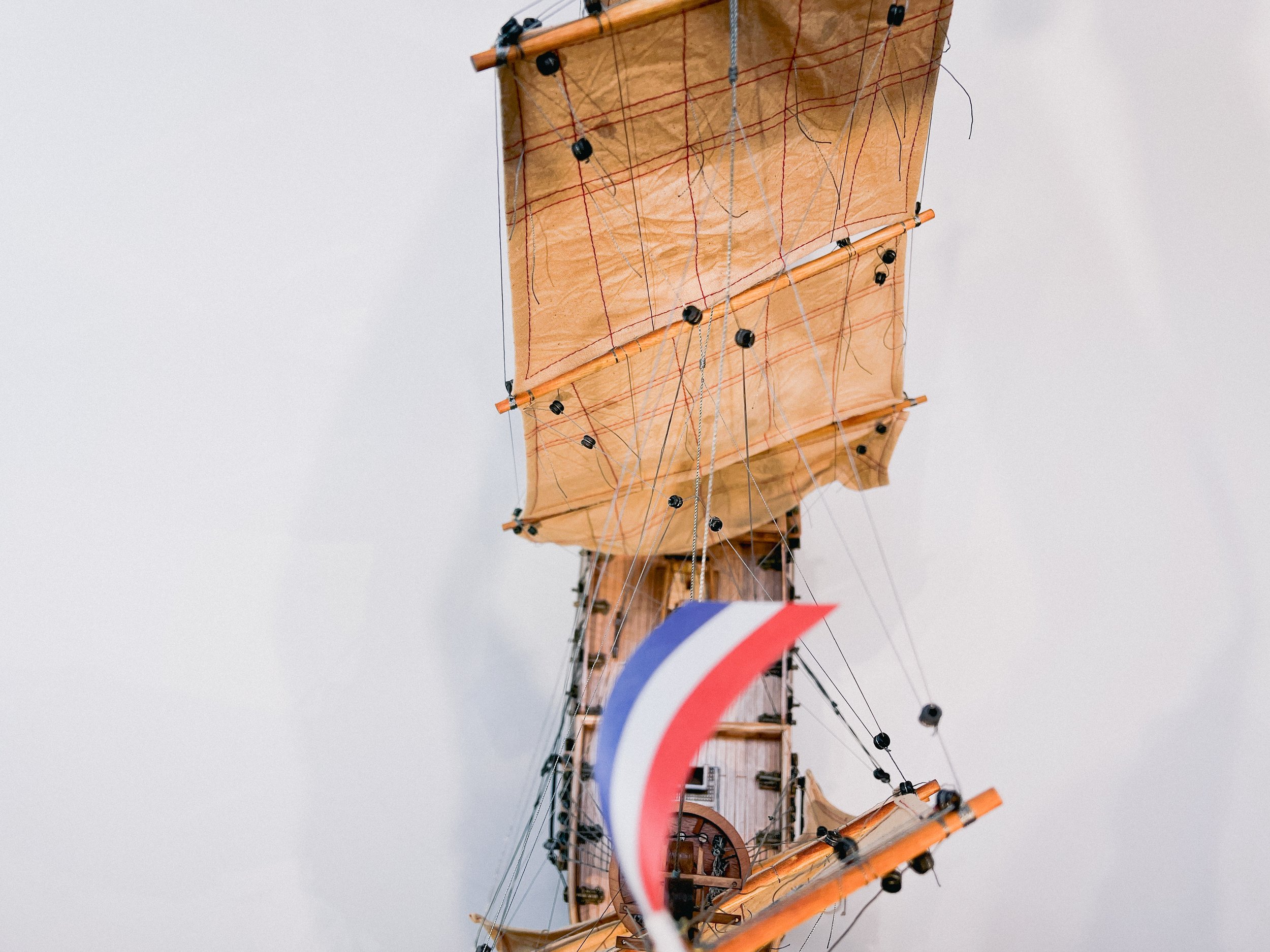

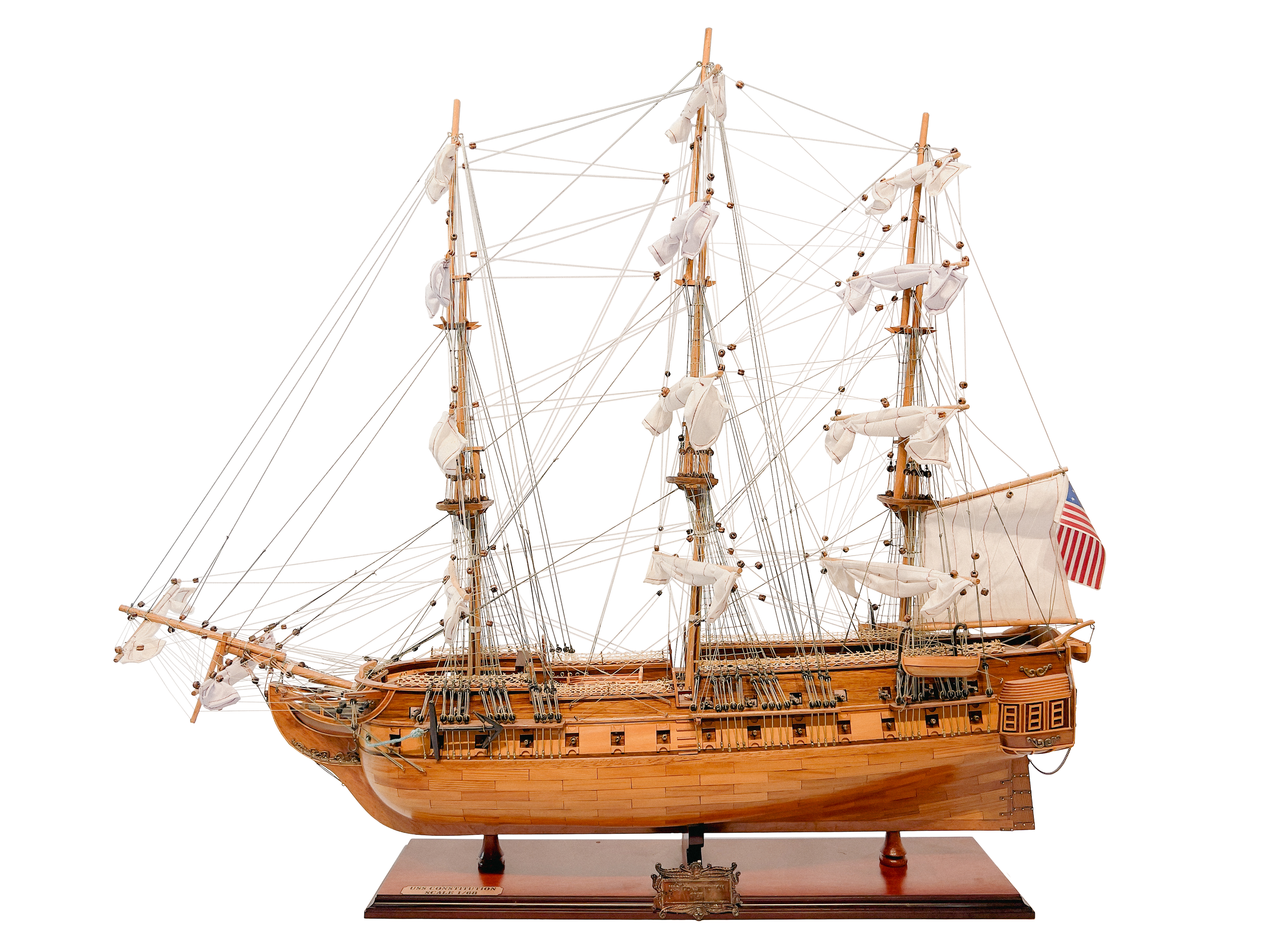

zoom in on model

1666– 1683

friesland(WEstfriesland)

Scale 1/75

Credit: Museum of Military Models, Clyde, Texas. Private Collection of Warren D. Harkins.ON VIEW

General Characteristics

Class and type:

Second Rate - Full Rigged Ship, Ship of the Line

Length:

160' 0" Amsterdam ft - 45.296 m (148′ 7″ Imperial) Gundeck

40' 0" Amsterdam ft 11.324 m (37′ 1″ Imperial) Breadth

14' 5 ½" Amsterdam ft 3.9763 m (13′ 0″ Imperial) Depth in Hold

7' 8 ¼" Amsterdam ft 1.9881 m (6′ 6″ Imperial) Height Between Decks

Armament:

1673:

Broadside Weight = 528 Dutch pound (574.992 lbs 260.8848 kg)

6 Dutch 36-pounder, 20 Dutch 18-pounder, 28 Dutch 12-pounder, 24 Dutch 6-pounder

1683:

Broadside Weight = 552 Dutch pound (601.128 lbs 272.7432 kg)

6 Dutch 36-pounder, 26 Dutch 18-pounder, 24 Dutch 12-pounder, 20 Dutch 6-pounder, 4 Dutch 3-pounder

Crew Complement:

1666: 350 - 300 sailors, 50 soldiers

1673: 324

Description

Friesland (/ˈfriːzlənd/ FREEZ-lənd; Dutch: official West Frisian: Fryslân) or Westfriesland, historically and traditionally known as Frisia or Groot Frisia, named after the Frisians, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. This second-rate ship was for the Admiralty of the Noorderwartier. It officially launched in 1666, where it engaged in many naval battles in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It wrecked in 1683 with no further information on why or how.

This particular ship was part of a list of “Ship of the Line” of the Dutch Republic or sailing warships which formed the Dutch battlefleet. It covers ships built from about 1623 (there are few reliable records of individual earlier warships) until the creation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in March 1815, including the period of the French-controlled Batavian Republic, nominal Kingdom of Holland and direct French annexation between 1795 and 1813. It excludes frigates and lesser warships.

The Burning of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672 The Battle of Solebay was the opening battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672-74.Ownership & Province

-

Name: Westfriesland or West Friesland

Namesake: Fryslân - Frisia - Groot Frisia

Ordered: Admiralty of the Noorderwartier

Shipyard: Unknown

Launched: 1666

Fate: Wrecked in 1683

Ship Commanders:

1666: Kapitein, Adriaan Dirckszoon Houttuijn

1672: Johan Belgicus, Graaf van Hoorne

1673: Kapitein, Jan Heck

Flag Officer:

1666-1667: Lieutenant-admiraal, Jan Corneliszoon Meppel

History & Related Content

The Five Admiralties

Administratively and politically, until 1795 there was not a single Dutch Navy but five distinct Admiralties. In the south was the Admiralty of Zeeland covering the Province of Zeeland (indicated by "(Z)" preceding a ship's name in the list below). Next were three covering the Province of Holland - the Admiralty of the Maas (or "Maze") in the south of Holland, centred on Rotterdam (indicated by "(M)"), the Admiralty of Amsterdam in the centre of the Province (indicated by "(A)"), and the Admiralty of the Noorderkwartier in the north of Holland (indicated by "(N)"). The fifth was the Admiralty of Friesland covering the Province of Friesland (indicated by "(F)"), albeit with fewer ships than the other four Admiralties. Each Dutch warship belonged exclusively to one or other of the five Admiralties, although in the 17th century the Dutch fleet included many ships of mercantile ownership, particularly those belonging to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The names of Dutch warships were often common to several Admiralties, so that there were vessels bearing the same name in different Admiralties at the same time.

Armament was often changed, so the number of guns mounted in any ship frequently varied from year to year. During the 1650 - 1680 period, many Dutch ships of the line were "up-gunned", ending with significantly more guns (or guns of larger calibres) than when they first came into service.

Built 1660 to 1680

With the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Staten-Generaal ordered the construction of twenty-four large ships, with a second group of twenty-four being added soon after. This programme, which was all built in the period 1664 to 1667, included ten ships of 160 (Amsterdam) feet length or more, now forming the 1st Charter.

1st Charter

(A) Hollandia 82 guns (1665, 165 ft) - Cornelis Tromp's flagship at the St James Day Battle, sold to be broken up in 1694

(M) Zeven Provinciën 80 guns (1665, 163 ft) - Michiel de Ruyter's flagship at the St James Day Battle, broken up 1694

(N) Pacificatie 80 (1665, 160 ft) - Volckert Schram's flagship at the St James Day Battle

(M) Eendracht 76-80 (1666, 160 ft) - Aert van Nes's flagship at the St James Day Battle

(N) Westfriesland 78 (1666, 160 ft)- Jan Meppel's flagship at the St James Day Battle

(A) Gouden Leeuw 80 (1666, 170 ft) - Cornelis Tromp's flagship at the Battle of Texel

(A) Olifant (or Witte Oliphant) 80 (1666, 171 ft)

(A) Dolphijn 84 (1667, 171 ft)

(M) Voorzichtigheid 80-84 (1667, 165 ft) - renamed (rebuilt?) Wakende Kraan in 1677

(M) Vrijheid 80 (1667, 165 ft)

2nd Charter and below

This list includes ships of the line built (all for the Amsterdam Admiralty) in the period 1661 to 1663, prior to the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

(A) Liefde 70 (1661, 140 ft) – broken up 1666

(A) Geloof 60 (1661, 140 ft) – broken up 1676

(A) Wakende Boei 48 (1661, 130 ft) – broken up 1675

(A) Harderwijk 46 (1662, 133 ft) – broken up 1693

(A) Provincie van Utrecht 60 (1663, 145 ft) – broken up 1691

(A) Waasdorp 68 (1663, 150 ft) – broken up 1666

(A) Spiegel. 66 guns (1663, 156 ft x 41 ft x 15 ft) – Built at Amsterdam by Jan van Rheenen, this was the first three-decker in Dutch service, although on the upper deck she was not armed in the waist; the name means either "mirror" or "transom" in Dutch. This fairly 'short' three-decker (classed as 2nd Charter) was armed with 6 × 24-pdrs and 16 × 18-pdrs on the lower deck, 24 × 12-pdrs on the middle deck, and 20 × 6-pdrs on the upper and quarter decks. Served as flagship of Vice-Admiraal Michiel de Ruyter from 1664 until August 1665, including his expedition to the Caribbean and West Africa from 1664 to 1665; broken up in 1676.

(A) Akerboom 60 (1664, 140 ft) – wrecked 1689

(A) Gideon 60 (1664, 140 ft) – broken up 1689

(A) Steenbergen 64 (1664, 150 ft) – sunk at Battle of Palermo in 1676

(N) Monnikendam 62 (1664, 140 ft) – wrecked 1683

(N) Noorderkwartier 60 (1664, 136 ft) – sold 1686

(A) Kalandsoog 68 (1665, 150 ft) – broken up 1691

(A) Deventer 62 (1665, 148 or 150 ft) – wrecked 1673

(F) Vredewold 60 (1665, 140 ft)

(A) Gouden Leeuwen 50 (1665, 141 ft)

(A) Beschermer 54 (1665, 1413⁄4 ft)

(A) Essen 50 (1665, 142 ft)

(Z) Zierikzee 60 (1665, 145 ft)

(M) Delfland 70 (1665)

(F) Frisia (or Groot Frisia) 74 (1665, 150 ft)

(F) Prins Hendrik Casimir 74 (1665, 150 ft)

(A) Wapen van Utrecht 62 (1665, 152 ft)

(A) Gouda 72 (1665, 1571⁄2 ft)

(A) Komeetster 70 (1665, 1521⁄2 ft))

(A) Reigersbergen (or Blauwe Reiger) 74 (1665, 156 ft)

(Z) Walcheren 70 (1665, 155 ft)

(Z) Gekroonde Burgh 70 (1666, 150 ft)

(M) Ridderschap 72 (1666, 150 ft)

(N) Wapen van Enkhuizen 72 (1665, 150 ft)

(F) Groningen 72 (1666, 150 ft)

(F) Zevenvolden 76 (1666)

(F) Sneek 65 (1666, 150 ft)

(Z) Tholen 60 (1666, 145 ft)

(Z) Domburg 60 (1666, 145 ft)

(N) Alkmaar 62 (1666, 140 ft)

(M) Schieland 54 (1666, 140 ft)

(M) Wassenaar 56 (1666, 140 ft)

(M) Gelderland 72 (1666, 150 ft)

(M) Maagd van Dordrecht 68 (1666, 150 ft)

(N) Prins van Oranje (or Jonge Prins) 62 (1666, 150 ft)

(N) Eenhoorn (or Wapen van Hoorn) 70 (1667)

(A) Woerden 72 (1667, 150 ft)

(N) Monnikendam 70 (1671)

(A) Oudshoorn 70 (1672)

Note the earlier Oudshoorn of 70 guns was the prize Swiftsure captured from the English at the Four Days Battle in 1666

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of naval wars between England and the Dutch Republic, driven largely by commercial disputes.

Despite several major battles, neither side was able to score a decisive victory, and by the end of 1666 the war had reached stalemate. Peace talks made little progress until the Dutch Raid on the Medway in June 1667 forced Charles II to agree to the Treaty of Breda.

By eliminating a number of long-standing issues, the terms eventually made it possible for England and the Dutch Republic to unite against the expansionist policies pursued by Louis XIV of France. In the short-term however, Charles' desire to avenge this setback led to the Third Anglo-Dutch War in 1672.

Four Days' Battle

The Four Days' Battle was a naval engagement fought from 11 to 14 June 1666 (1–4 June O.S.) during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It began off the Flemish coast and ended near the English coast, and remains one of the longest naval battles in history.

The Royal Navy suffered significant damage, losing around twenty ships in total. Casualties, including prisoners, exceeded 5,000 with over 1,000 men killed, including two vice-admirals, Sir Christopher Myngs and Sir William Berkeley. Almost 2,000 were taken prisoner including Vice-admiral George Ayscue.

Dutch losses were four ships destroyed by fire and over 2,000 men killed or wounded, among them Lieutenant Admiral Cornelis Evertsen, Vice Admiral Abraham van der Hulst and Rear Admiral Frederik Stachouwer. Although a clear Dutch victory, the surviving English ships were able to beat off an attempt to destroy them at anchor in the Thames estuary in early July. After quickly refitting, on 25 July the English defeated the Dutch in the St. James's Day Battle.

Jan Cornelisz Meppel, Lieutenant-Admiral of Holland and West-Friesland oil on canvas 106.5 × 87.5 cm signed: AEtatis 52. 1661 JRootiusl - Jan Albertsz Rotius.The Four Days Battle by Abraham Storck.St. James’ Day Battle

The St James' Day Battle took place on 25 July 1666 (4 August 1666 in the Gregorian calendar), during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It was fought between an English fleet commanded jointly by Prince Rupert of the Rhine and George Monck, and a Dutch force under Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter.

Background

After the Dutch had inflicted enormous damage on the English fleet in the Four Days Battle of 1–4 June 1666 which is normally considered a Dutch victory, the Dutch leading politician grand pensionary Johan de Witt ordered Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter to carry out a plan that had been prepared for over a year: to land in the Medway to destroy the English fleet while it was being repaired in the Chatham dockyards. For this purpose ten fluyt ships carried 2,700 marines of the newly created Dutch Marine Corps, the first in history. Also De Ruyter was to combine his fleet with the French one.

The French however did not show up and bad weather prevented the landing. De Ruyter had to limit his actions to a blockade of the Thames. On the 1st of August he observed that the English fleet was leaving port - earlier than expected. Then a storm drove the Dutch fleet back to the Flemish coast. On the 3rd De Ruyter again crossed the North Sea, leaving behind the troop ships.

Battle

First Day

In the early morning of 25 July, the Dutch fleet of 88 ships discovered the English fleet of 89 ships near North Foreland, sailing to the north. De Ruyter gave orders for a chase and the Dutch fleet pursued the English from the southeast in a leeward position, as the wind blew from the northwest. Suddenly, the wind turned to the northeast. The English commander, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, then turned sharply east to regain the weather gauge. De Ruyter followed, but the wind fell and the fleet fell behind. The Dutch van, commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Johan Evertsen, was becalmed and drifted away from the line of battle, splitting De Ruyter's fleet in two. This awkward situation lasted for hours; then, again, a soft breeze began to blow from the northeast. Immediately, the English van, commanded by Thomas Allin, and part of the centre formed a line of battle and engaged the Dutch van, still in disarray.

The Dutch failed to form a coherent line of battle in response, and ship after ship was mauled by the combined firepower of the English line. Vice-Admiral Rudolf Coenders was killed, and Lieutenant-Admiral Tjerk Hiddes de Vries had an arm and a leg shot off, yet still tried to bring cohesion to his force — but to no avail. Unable to reach them with his centre, the horrified De Ruyter saw the Frisian ships drifting to the south, now no more than floating wrecks full of dead, the moans of the dying clearly audible above the other sounds of battle.

With the Dutch van defeated, the English converged to deliver the coup-de-grâce to De Ruyter's centre. George Monck, accompanying Rupert, predicted that De Ruyter would give two broadsides and run, but the latter put up a furious fight on the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën. He withstood a combined attack by Royal Sovereign and Royal Charles and forced Rupert to leave the damaged Royal Charles for Royal James. The Dutch centre's resistance enabled the seaworthy remnants of the van to make an escape to the south.

Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp, commanding the Dutch rear, had from a great distance seen the disaster for the Dutch fleet evolve. Annoyed by what he saw as a lack of competence, he decided to give the correct example. He turned sharply to the west, crossed the line of the English rear, under the command of Jeremiah Smith, separating it from the rest of the English fleet and then, having the weather gauge, kept on attacking it rabidly until at last the English were routed and fled to the west. He pursued well into the night, destroying HMS Resolution with a fireship. After Tromp three times shot the entire crew from its rigging, Smith's flagship HMS Loyal London caught fire and had to be towed home. The vice commander of the English rear was Edward Spragge, who felt so humiliated by the course of events that he became a personal enemy of Tromp. He would later be killed pursuing Tromp in the Battle of the Texel.

Second Day

On the morning of 26 July, Tromp broke off pursuit, well-pleased with his first real victory as a squadron commander. During the night, a ship had brought him the message that De Ruyter had likewise been victorious, so Tromp was in a euphoric mood. That abruptly changed upon the discovery of the drifting flagship of the dying Tjerk Hiddes de Vries. Suddenly he feared that his ship was now the only remnant of the Dutch fleet and that he was in mortal peril. Behind him, those ships of the English rear still operational had again turned to the east. In front, the other enemy squadrons surely awaited him. On the horizon, only English flags were to be seen. Manoeuvring wildly, Tromp, drinking a lot of gin to restore his nerve, dodged any attempt to trap him and brought his squadron safely home in the port of Flushing on the morning of 26 July. There, to great mutual relief, he discovered the rest of the Dutch fleet.

It took Tromp six hours to gather enough courage to face De Ruyter. It was obvious to him that he should never have allowed himself to get completely separated from the main force. Indeed, De Ruyter, not being his usual charitable self, immediately blamed him for the defeat and ordered Tromp and his subcommanders Isaac Sweers and Willem van der Zaan from his sight, and told them to never again set foot on De Zeven Provinciën. The commander of the Dutch fleet still had not mentally recovered from the events of the previous day.

On the morning of 5 August, after a short summer's night, De Ruyter discovered that his position had become hopeless. Lieutenant-Admiral Johan Evertsen had died after losing a leg, De Ruyter's force was now reduced to about forty ships, crowding together and most of these were inoperational, being survivors of the van. Some fifteen good ships had apparently deserted during the night. A strong gale from the east prevented an easy retreat to the continental coast, and to the west the British van and centre (about fifty ships) surrounded him in a half-circle, safely bombarding him from a leeward position.

De Ruyter was desperate. When his second-in-command of the centre, Lieutenant-Admiral Aert Jansse van Nes visited him for a council of war, he exclaimed: "With seven or eight against the mass!" He then sagged, mumbling: "What's wrong with us? I wish I were dead." His close personal friend Van Nes tried to cheer him up, joking: "Me too. But you never die when you want to!" No sooner had both men left the cabin than the table they had been sitting at was smashed by a cannonball.

The English, however, had their own problems. The strong gale prevented them from closing with the Dutch. They tried to use fire ships, but these, too, had trouble reaching the enemy. Only the sloop Fan-Fan, Rupert's personal pleasure yacht, rowed to the Dutch flagship De Zeven Provinciën to harass it with its two little guns, much to the hilarious laughter of the English crews.

When his ship had again warded off an attack by a fireship (the Land of Promise) and Tromp still did not show up, for De Ruyter tension became unbearable. He sought death, exposing himself deliberately on the deck. When he failed to be hit, he exclaimed: "Oh, God, how unfortunate I am! Amongst so many thousands of cannonballs, is there not one that would take me?" His son-in-law, Captain of the Marines Johann de Witte, heard him and said: "Father, what desperate words! If you merely want to die, let us then turn, sail in the midst of our enemies and fight ourselves to death!". This brave but foolish proposal brought the Admiral back to his senses, for he discovered that he was not so desperate and answered: "You don't know what you are talking about! If I did that, all would be lost. But if I can bring myself and these ships safely home, we'll finish the job later."

Then the wind, that had brought so much misfortune to the Dutch, saved them by turning to the west. They formed a line of battle and brought their fleet to safety through the Flemish shoals, Vice-Admiral Adriaen Banckert of the Zealandic fleet covering the retreat of all damaged ships with the operational vessels, the number of the latter slowly growing as it turned out that only very few ships had actually deserted in the night; most had merely drifted away, and now, one after the other, they rejoined the battle.

Aftermath

The battle was a clear English victory. Dutch casualties were initially thought to be enormous, estimated immediately after the battle of about 5,000 men, compared with 300 English killed; later, more precise information showed that only about 1,200 of them had been killed or seriously wounded. The Dutch only lost two ships: De Ruyter had been successful at saving almost the complete van, only Sneek and Tholen struck their flag. Tholen was the flagship of admiral Banckert who had moved his flag to another vessel. Both ships were burnt by the English. The Dutch could quickly repair the damage. The twin disasters of the Great Plague of London and the Great Fire of London, combined with his financial mismanagement, left Charles II without the funds to continue the war. In fact, he had had only enough reserves for this one last battle.

While the Dutch fleet was undergoing repairs, Admiral Robert Holmes, aided by the Dutch traitor Laurens van Heemskerck, penetrated the Vlie estuary, burnt a fleet of 150 merchants (Holmes's Bonfire) and sacked the town of Ter Schelling (the present West-Terschelling) on the Frisian island of Terschelling. Fan-Fan was again present.

In the Republic, the defeat also had a far-reaching political effect. Tromp was the champion of the Orangist party; now that he was accused of severe negligence, the country split over this issue. To defend himself, Tromp let his brother-in-law, Johan Kievit, publish an account of his conduct. Shortly afterward, Kievit was discovered to have planned a coup, secretly negotiating a peace treaty with the English king. He fled to England and was condemned to death in absentia; Tromp's family was fined and he himself forbidden to serve in the fleet. In November 1669, a supporter of Tromp tried to stab De Ruyter in the entrance hall of his house. Only in 1672 would Tromp have his revenge, when Johan de Witt was murdered; some claim Tromp had had a hand in this. The new ruler, William III of Orange, succeeded, with great difficulty, in reconciling De Ruyter with Tromp in 1673.

Engraving showing the St. James Day battle August 4th, 1666, between English and Dutch ships.The Dutch Fleet Assembling Before the Four Days’ Battle of 11-14 June 1666." Made by Willem van de Velde the Younger in 1670. The ‘Liefde’ (Love) in the foreground on the left side is a 70-cannon man-of-war ship. On the right side is the “Gouden Leeuw” (Golden Lion) with two back-to-back lions on its stern. These are famous ships of the Admiralty of Amsterdam.The Four Days Fight, 1–4 June 1666, by Pieter Cornelisz van Soest.Court martial of the Dutch fleet for the Four Days Marches Battle in 1666. Willem van de Velde II.St. James Day Fight August 4th, 1666, by Wenceslaus Hollar.Battle of Solebay

The Battle of Solebay took place on 6 June 1672 New Style, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, near Southwold, Suffolk, in eastern England. A Dutch fleet under Michiel de Ruyter attacked a combined Anglo-French force in one of the largest naval battles of the age of sail. Fighting continued much of the day, but ended at sunset without a clear victory. However, the scattered Allied fleet had suffered far more damage and was forced to abandon any plans to land troops on the Dutch coast.

Prelude

In 1672, both France and England declared war on the Dutch Republic, on the 6 and 7 April respectively. Johan de Witt, the Dutch Grand Pensionary, still harbored some hope for successful negotiations, especially with the support of influential anti-Catholic English figures such as Sir William Temple and the Earl of Sandwich. However, Louis XIV of France had already revealed his true intentions during a sharp address to the Dutch ambassador, Pieter de Groot, at the New Year's reception at his court. As French troops advanced towards the Rhine and the armies of Münster and Cologne penetrated the eastern provinces, the combined English and French fleets were poised to strike the Republic from the sea.

The joint Anglo-French fleet consisted of 93 warships (sources vary), 35,000-40,000 men and 6,158 cannon. The Allies under the Duke of York and Vice-Admirals Earl of Sandwich and Comte Jean II d'Estrées planned to blockade the Dutch in their home ports and deny the North Sea to Dutch shipping. The Dutch had at their disposal a fleet of 75 warships, 20,738 men and 4,484 cannon, commanded by Lieutenant-Admirals Michiel de Ruyter, Adriaen Banckert and Willem Joseph van Ghent. The Dutch had hoped to repeat the success of the Raid on the Medway and a frigate squadron under Van Ghent sailed up the Thames in May but discovered that Sheerness Fort was now too well prepared to pass. The Dutch main fleet came too late, mainly due to coordination problems between the five Dutch admiralties, to prevent a joining of the English and French fleets. It followed the Allied fleet to the north, which, unaware of this, put in at Solebay to refit.

Battle

On 7 June at dawn, around 5 a.m., off Orfordness, De Ruyter suddenly appeared in the sight of the Allied fleet. Although a lack of wind prevented De Ruyter from launching an attack with his fireships, the confusion among the suddenly alarmed English and French was still significant. Officers and sailors, still on shore, were quickly signaled to return to their ships, and the Anglo-French fleet immediately set sail, though in less than ideal order. The French, whether through accident or design, found themselves in the rear and considerably south of the English, whose vanguard under Sandwich and middle squadron under York lay close to the coast.

De Ruyter had employed a new formation, creating from the various squadrons under Jan van Brakel a "forlorn hope" squadron of 18 ships and 18 fireships, which was to attack the enemy ahead of the main force and attempt to cause confusion with its fireships. However, this failed, and the battle had to be fought between the main squadrons. Having the weather gauge, De Ruyter attacked the enemy around 8 a.m. at full speed. He himself directing his attack against the middle squadron as usual. The Duke of York, who commanded the Allied middle squadron, and De Ruyter fiercely bombarded each other. York was forced to move his flag twice, finally to London, as his flagships Prince and St Michael were taken out of action. Prince was crippled by De Ruyter's flagship De Zeven Provinciën in a two-hour duel. De Ruyter was accompanied by the representative of the States-General of the Netherlands, Cornelis de Witt (the brother of Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt) who bravely remained seated on the main deck, although half of his guard of honour standing next to him was killed or wounded.

In the meantime Banckert had taken on the French squadron under d'Estrées, which flew the white flag. The French, quite far away from the English squadrons, steered south followed by Banckert. They fiercely exchanged fire throughout the day, inflicting severe damage on each other without significantly influencing the battle's outcome. This later led to various speculations about the actual separation of the two squadrons, with many wrongly attributing it to secret mutual agreements or D'Estrees' reluctance to participate more fully in the battle, possibly related to a supposed mission to weaken the two great maritime powers against each other. Nevertheless, the Superbe was heavily damaged and des Rabesnières killed by fire from Enno Doedes Star's Groningen; total French casualties were about 450.

The battle between squadrons of Sandwich and Van Ghent was no less bloody than that between those of York and De Ruyter. Here, too, the fiercest fighting took place between the admiral's ships and their "seconds." The flagship of Sandwich, HMS Royal James, was first fiercely engaged by Lieutenant-Admiral Van Ghent, who in 1667 had executed the Raid on the Medway, on Dolfijn. Van Brakel, who actually belonged to De Ruyter's squadron, took it upon himself to engage Sandwich's ship with Groot Hollandia to aid the heavily attacked Van Ghent. He incessantly pounded the hull of Royal James for over an hour and bringing her into such a condition that Lord Sandwich considered to strike his flag but decided against it because it was beneath his honour to surrender to a mere captain of low birth. Van Ghent was killed around 10 a.m. in this ship battle, and the desperate Sandwich, who could not board Groot Hollandia due to a lack of crew, finally managed to free himself from Van Brakel at low tide. But Royal James now drifted away, sinking, and was attacked by several fire ships. She sank two, but a third commanded by Van den Ryn, the same captain who had cut through the chain at the Medway, set the Royal James on fire. Its approach shielded by Vice-Admiral Isaac Sweers's Oliphant. After nine-tenths of its thousand crew members had been killed or wounded Sandwich, abandoned by part of his own squadron under Joseph Jordan, who had engaged vice admiral Volckert Schram's division, remained on his burning ship until he met his death in the waves. He and his son-in-law Philip Carteret drowned trying to escape when his sloop collapsed under the weight of panicked sailors jumping in; his body washed ashore, only recognisable by the scorched clothing still showing the shield of the Order of the Garter. The battle continued for hours, with Van Panhuys, Van Ghent's captain, flying his flag on De Witt's express orders to prevent panic. Despite this, the death of the lieutenant admiral soon became known, causing significant disruption in his squadron.

In the centre Lieutenant-Admiral Aert Jansse van Nes aboard Eendracht first duelled Vice-Admiral Edward Spragge on HMS London and then was attacked by HMS Royal Katherine. The latter ship was then so heavily damaged that Captain John Chichely struck her flag and was taken prisoner; the Dutch prize crew however got drunk on the brandy found and allowed the ship to be later recaptured by the English. Van Ghent's death presented a formidable challenge for De Ruyter, who was now also under attack from some of the ships from Sandwich's squadron commanded by Jordan. Meanwhile, York had to transfer from the damaged St Michael to the London, Spragge's flagship, due to severe leaks. The battle centered on the two middle squadrons. The two fleets, under light winds, drifted southward along the banks of Lowestoft and as far as Aldbrough, engaged in intense and chaotic combat. By late evening, De Ruyter managed to maneuver behind the English centre. He now headed toward Banckert, while York maneuvered towards D'Estrees. During this maneuver, De Ruyter encountered a smaller vessel, Rainbow, commanded by Captain James Storey, which he left severely damaged after a brief skirmish.

Around 9 p.m., with the onset of darkness, the battle ended, remaining largely undecided, although the Allied fleet had suffered far more damage. The Battle of Solebay, according to De Ruyter himself, "was sharper and more prolonged" than any naval battle he had ever witnessed. Losses had also been heavy on the Dutch side: one Dutch ship, Jozua, was destroyed and another, Stavoren, captured, a third Dutch ship, Wassenaer, had an accident during repairs immediately after the battle and blew up.

In a strategic sense, it was however a clear Dutch victory as it deterred Anglo-French plans to blockade Dutch ports and land troops on the Dutch coast. Tactically both sides sustained heavy damages; two English ships were sunk, including the fleet's flagship the Royal James, as well as two French ships sunk. The Dutch also lost two large ships, in addition to many fire ships.

The fleets met again at the Battle of Schooneveld in 1673.

French flagship Saint-Philippe prior to the Battle of Solebay.St. James Day Fight August 4th, 1666, by Wenceslaus Hollar.Cornelis de Witt watches the battle on board of De Zeven Provinciën.The Burning of the Royal James, by Van de Velde.